The Keeley Institute In the late 19th century, as opium and alcohol addiction rates soared in...

Koger Island: A Glimpse Into the Past

Just south of where the Natchez Trace bridge spans the Tennessee River lies Koger Island, a landscape rich with history, both ancient and antebellum. The island is named after William and Martha Koger, prominent figures in the region’s history, whose large plantation sat just north of the island. Their arrival in the area marked a period of significant growth, but long before the Kogers laid claim to the land, it had already been home to indigenous peoples whose legacy still echoes through the soil.

William Koger and His Plantation

William and Martha (Westmoreland) Koger arrived in the fertile farmland west of Florence during the early 19th century. In the 1820s, they settled on what was known as the "Colbert Reserve" or "The Bend," a lush area situated on the north side of the Tennessee River. This land would become the cornerstone of the Koger family’s wealth. By the time of the 1850 census, William Koger was listed as a "farmer," though the term doesn’t quite capture the extent of his holdings or influence. With personal property valued at over $11,000—a significant sum in that era—Koger had under cultivation 480 acres of land, including the 150-acre island in the Tennessee River that would bear his name.

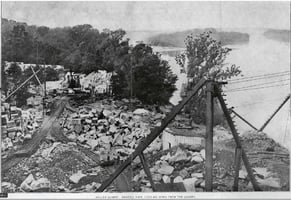

Though it may seem humble today, Koger Island was once a larger and more integral part of the Tennessee River landscape. Its size was reduced after 1938 when the Tennessee Valley Authority’s controlled flooding reshaped much of the river’s surrounding areas. The flooding, aimed at reducing the damage caused by natural floods, submerged parts of the island and forever altered its appearance. Still, the lore of Koger Island runs deep, particularly in its connections to the Native American history that predates any European settlement.

The Shell Mound People and the Mississippian Civilization

Long before William and Martha Koger made the island a part of their plantation, it was inhabited by two distinct groups of indigenous people. The first to settle the area were the Shell Mound People, so named by archaeologists for their distinct method of creating massive earthworks from layers of shell and other refuse. These mounds, now mostly gone or buried under centuries of sediment, were essential parts of the Shell Mound People’s culture, likely serving as both ceremonial sites and living spaces.

Around 1,000 years ago, a more advanced civilization took root on Koger Island—the Mississippian people. The Mississippian Period, lasting from roughly AD 800 to 1600, was a time of great cultural and societal development across the southeastern United States. The people who lived on Koger Island during this time were part of a larger network of Mississippian societies known for their large, complex settlements and sophisticated systems of governance. They built impressive earthworks and mounds, and their society was structured in ways that modern archaeologists are still working to fully understand.

The Mortuary Practices of Koger Island

Archaeological work on Koger Island has revealed it was not just a place of daily life but also a significant burial ground. The island’s cemetery has long intrigued researchers. Christopher Peebles, a prominent archaeologist, was one of the first to analyze the Koger Island site through the lens of what’s called the Binford-Saxe mortuary program. This framework, commonly used to understand burial customs, links the way people are buried to their social status. Peebles’ work suggested that, like many Mississippian societies, the people buried on Koger Island held ranked positions in their communities, with burial practices reflecting their status.

However, more recent interpretations of the burial practices at Koger Island suggest a different understanding. Instead of being purely based on inherited rank or social hierarchy, the burials seem to reflect a society where status was earned through individual achievements. The placement of graves and the distribution of funerary objects, such as pottery or tools, also hint at a dual social structure. The deceased were either marked as members of one of two kinship groups or, in some cases, as outsiders to the community. These burial practices, and the artifacts found with them, reveal not only a complex society but also a deep sense of identity tied to both family and community roles.

William Koger and the Cruel Realities of Plantation Slavery

While William Koger is remembered for his wealth and the vast plantation he cultivated, his status as a slave owner is a crucial part of his legacy. Like many other plantation owners of the time, Koger saw slaves primarily as property, and their well-being was often secondary to his economic interests. Slave families, already fragile due to the inherent instability of their status, were subject to being split apart when it benefitted their owner. In fact, Koger's will directed that his slaves be divided among his wife, children, and grandchildren upon his death. This division of human lives could not be executed without tearing apart families, a common and cruel practice in the antebellum South. For Koger and many others, the financial interests and property rights of the master outweighed the personal bonds of the enslaved, revealing the harsh realities of life on plantations like his.